In his landmark 1981 book, After Virtue, philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre describes two people, separated by centuries, looking up at the night sky:

“The twentieth-century observer looks into the night sky and sees stars and planets; some earlier observers saw instead chinks in a sphere through which the light beyond could be observed. What each observer takes himself or herself to perceive is identified and has to be identified by theory-laden concepts.”

This is not a comment on advances in science or the merits of the empirical method. Rather, MacIntyre’s point is that the way we perceive the world, and act in it, is inextricably bound up in the theories we have about how the world works. Or to put it another way: How we think and what we do depends on the ‘big story’ we carry around in our heads.

And this really matters. For, as MacIntyre argues, “I can only answer the question ‘What am I to do?’ if I can answer the prior question ‘Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?’”

This was the question put to our staff as we began 2022 with our Term 1 All-Staff Professional Learning Day on Thursday 27 January. We continued our journey, which began a few years ago, to see how we might put our Brave Hearts Bold Minds philosophy of education into practice, and become experts in ‘Teaching for Character’.

This year, we focus on the ‘moral character’ qualities we aim to form in our boys: Our Faith and Tradition which inspire truth, honour, loyalty and commitment. Helping boys reflect on their understanding of right and wrong, of their place in the world, and their calling within it, starts with surfacing the stories that they (and we) believe about the world.

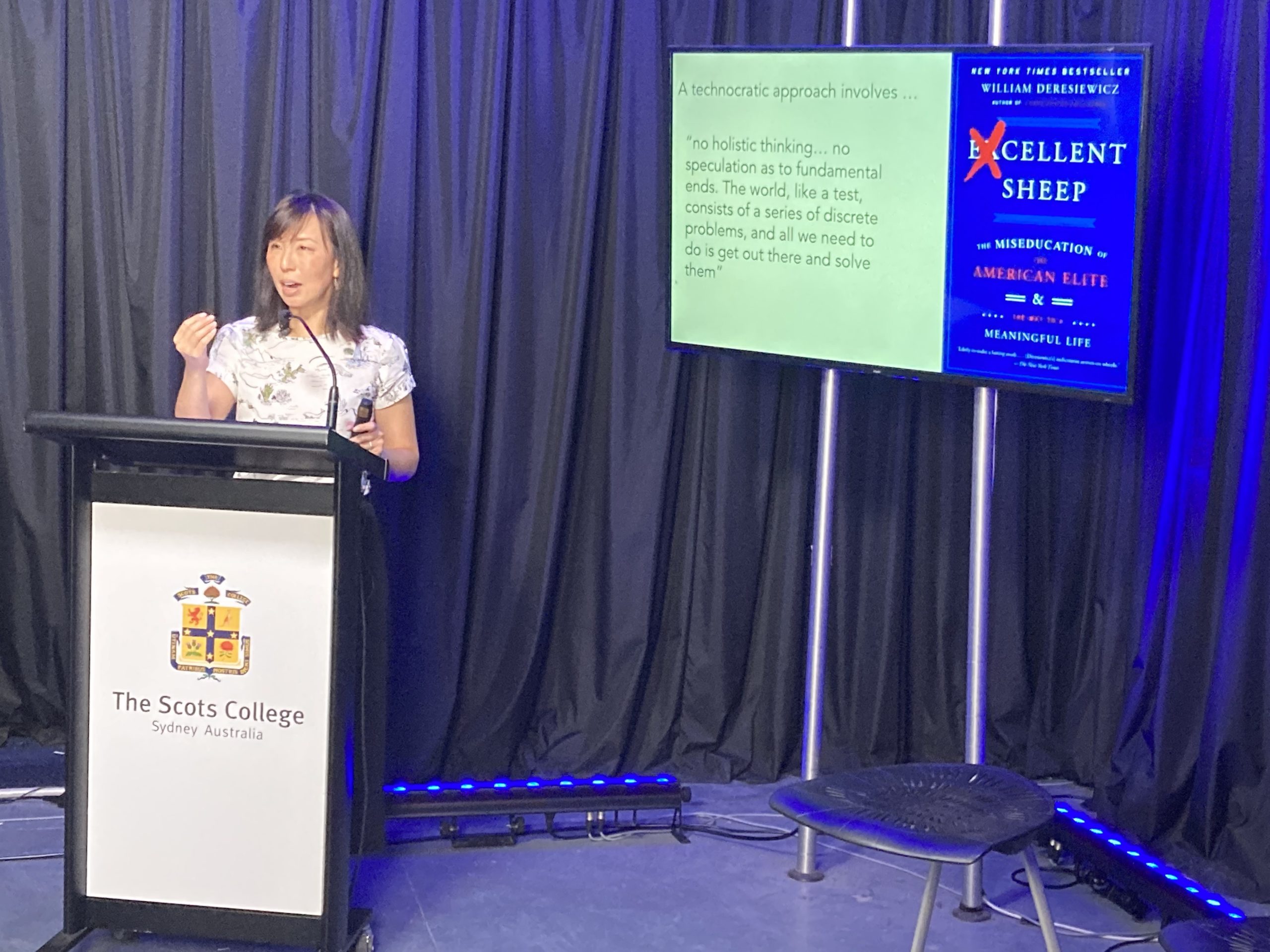

To help us do that, we were joined by Dr Justine Toh, Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity and author of the new book Achievement Addiction. Dr Toh engaged staff in a crash- course in cultural criticism, sketching out four powerful stories that shape our culture and considering their appeal and shortcomings.

First, there’s ‘the meritocratic story’, which says that you are what you achieve — so be sure to try harder. Next, there’s the ‘infinite browsing story’, which like Netflix, as in life, we keep our options open but are plagued by FOMO — the fear of missing out. Then there’s ‘the technocratic story’, where everything can be ‘solved’, except, of course, it cannot! And lastly, there’s the Christian story of people created in the image of God with infinite dignity and special purpose; a story that challenges the reductive view of the human condition so often presented to us.

Dr Toh challenged our staff to consider the ways in which we reinforce various stories about the world as we speak with the students. Making a high ATAR the ‘de facto’ goal of learning in the Senior years can teach boys that success is about hard work, and not also a result of the blessings of their birth and opportunities, leading them to look down on those who ‘did not make it’.

In undertaking group work, we can spell out how to relate well to those who we do not necessarily like, and so tell a story about how relationships across differences are more valuable than tribalism. In encouraging boys to immerse themselves in the humanities and creative arts (even if they tend to be more drawn to mathematics and the sciences), we can help them see that life is more about asking good questions than trying to find neat solutions.

Opportunities to teach character are everywhere. The great challenge that lies before us as teachers, and much more as parents and carers, is to get beneath the surface of boys’ behaviours to the beliefs that drive them. And it starts with asking that question of ourselves: What story am I living?

In the coming weeks, I look forward to sharing more about how we are helping our staff understand and practise expert character education at Scots, so that our boys will go on to live ‘a better story’.

Dr Hugh Chilton

Director of Research and Professional Learning